Beef Central Genetics editor Alastair Rayner, 24/08/2021

The strength of the 2021 spring bull sales has become a leading topic of conversation among producers, advisors and the rural media. While much attention is being placed on the records broken each week for individual animals and for sale averages, there are others asking where is the market heading?

As last week’s Beef Central genetics column explored, the actual relativity of bull prices has remained fairly consistent with heavy steer or feeder steer values.

While most producers are very conscious of the increased value that has been paid on their steers, surplus heifers, cull cows and older bulls, there are still some who wonder if they can get a new bull ‘a little cheaper’.

The issue of ‘price’ and ‘value’ is always an interesting one. There are many people who will swiftly point out that an expensive bull is not always the best one.

Again, this can become an emotive argument. Bull prices reflect a few interlinked factors. The base level is the actual cost that is associated with producing the animal and bringing it to a point of sale.

This cost must reflect the “running costs” over two years, including feed, veterinary & health costs, registration, and data collection costs. It also includes the expenditure around the sale – marketing, like the stud ads appearing on this page, and sale costs.

The value associated with these bulls comes from the genetic advantages on offer to producers. This value is based on the selection decisions and genetics a breeder has used within the herd to produce bulls which will change a herd. This can be harder to price, as genetic advantages are not necessarily equal.

At this point it’s important to recognise that the genetic needs of one producer are often very different and, in some cases, unique. And so, there are some who see a bull’s genetics as more desirable for their program and will value those accordingly on sale day.

Sale price is as much, then, a recognition that there is a pre-investment by the breeder combined with a need for those genetics by one or more buyers. To argue that the expensive bull isn’t the best one, fails in many ways to account for the commercial buyers’ individual needs and plans for the bull after purchase. In simplest terms, the bull may be the best for that individual for their specific purpose.

What is a ‘cheap’ bull?

So, what is a cheap bull? Again, it’s a relative question. Mostly it’s answered by a bull that was sold after the sale for the reserve price. However, there are often bulls that are sold between producers that have come from commercial programs and are valued at commercial rates. In comparative terms, that’s a cheap option.

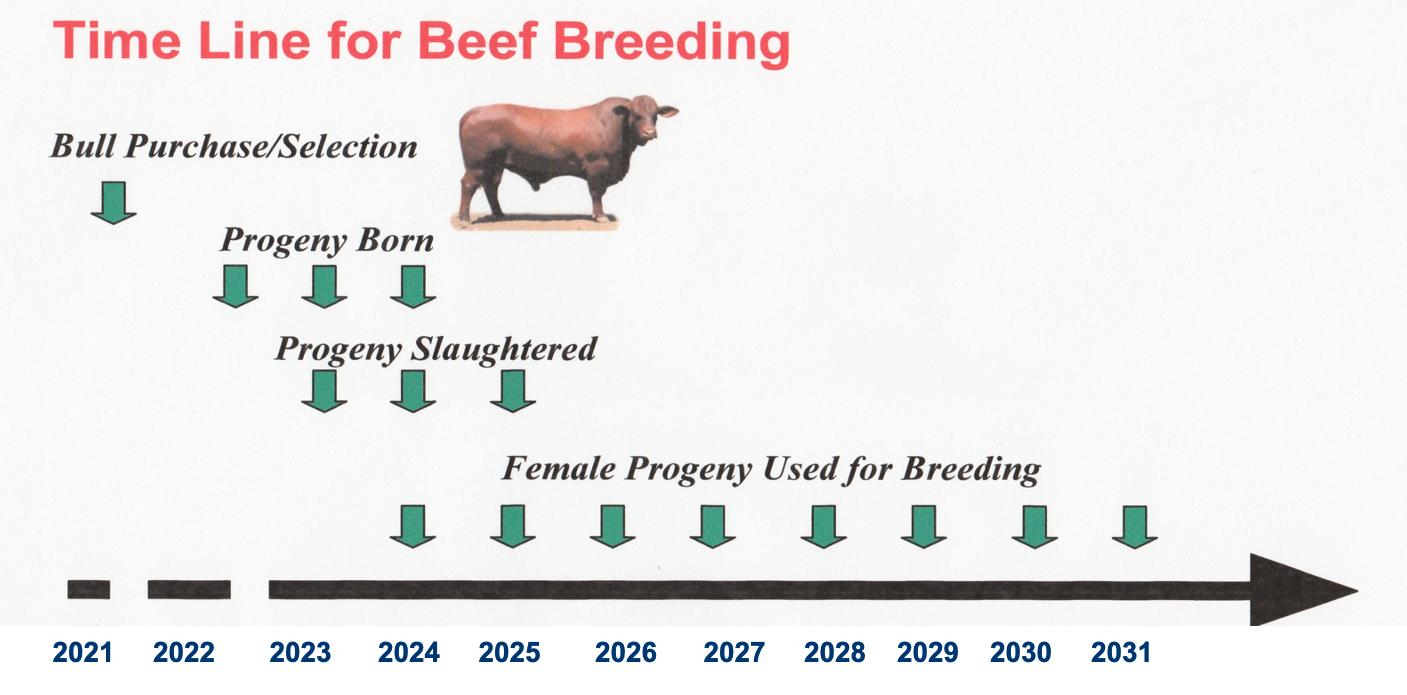

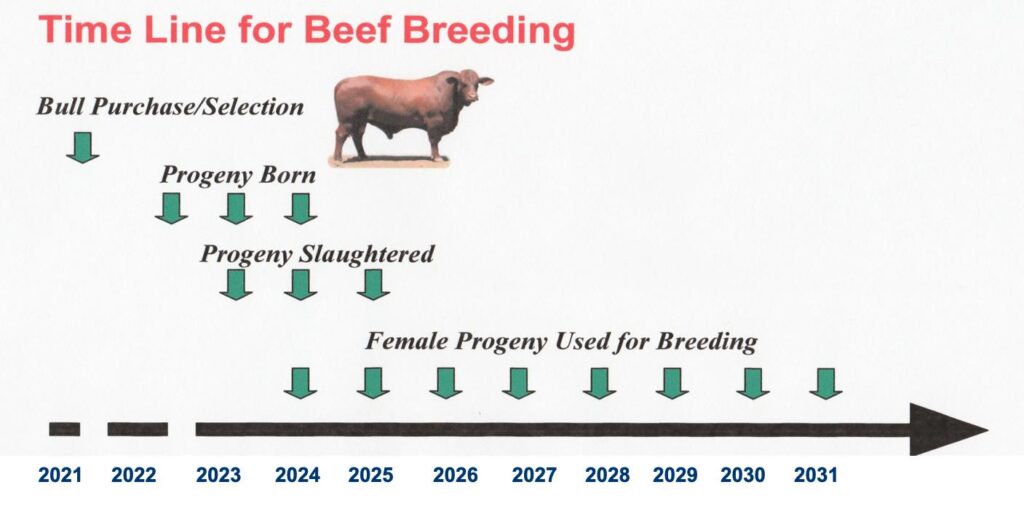

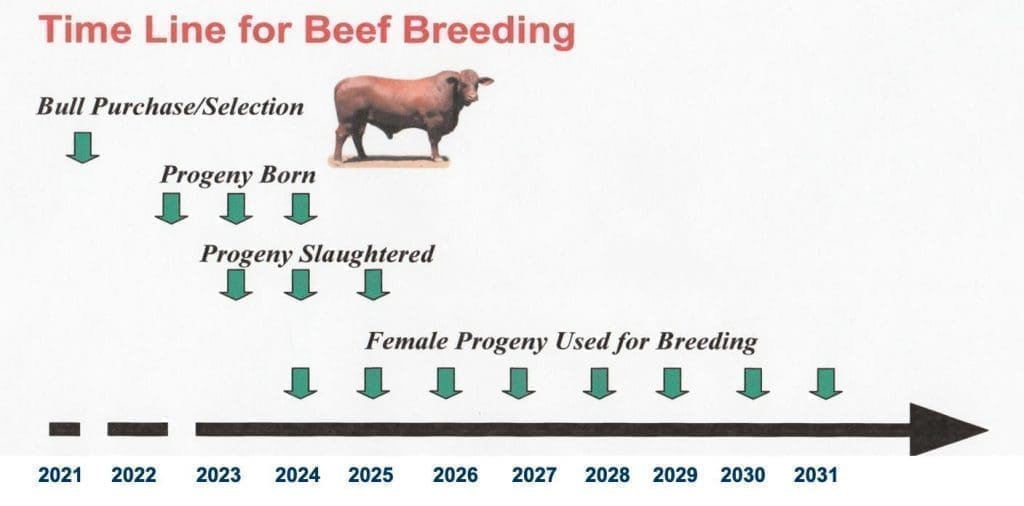

The problem with this approach – or the cheapest approach, is that it undervalues a breeding program. The timeline of breeding cattle is not a short one, as set out in this graphic:

Decisions on bulls have an impact that will stretch over a ten-year period. The immediate effect of a bull is the number of progeny that he sires, followed by the growth and market suitability of the steer calves produced. The longer-term effect is within the retention of heifers, where a bull’s daughters have a longer and greater contribution to a herd’s profitability than the three of four cohorts of steers may have done.

This long-term effect is really why producers should stop and consider whether a cheap bull is really worth it for the long-term productivity of their herd. Few breeding herds are interested only in producing crops of cattle to completely sell each year. Most will be looking to keep breeders and adjust their herd to grow faster, to be more suited to their environment or for other improvements.

A cheap bull often takes away that option. A bull with unknown genetics – either because he was born in a commercial (non-recorded) environment, or for some other reason can create long term damage to a herd.

These bulls are often purchased for their physical appearance, but may never produce calves that reflect their appearance. It’s impossible to know if the traits that are essential to keep a herd productive and profitable are those possessed by that bull.

The result could be slower growth, poorer structure, or temperament problems. So, while calves will be born, they may not be the ones that add the most value.

Equally, cheaper “passed-in” bulls have some disadvantages. True, they will generally have known genetic potential. However, that doesn’t mean those genetics are best suited to a specific buyer’s program. There is every potential for the bull to take the buyer’s herd in a less desirable direction.

The impact of introducing the wrong traits can take many years of work to correct. The time to correct these traits is one component. The other is the expense of purchasing corrective sires, to select and cull heifers with greater rigour than usual, as well as the ongoing impact of less productive and profitable sale animals.

When all things are considered against the timeline of breeding and the impact fewer desirable traits have on a system, it’s very hard to argue that a cheap bull is a good outcome for a herd.

Alastair Rayner is the Principal of RaynerAg, an agricultural advisory service based in NSW. RaynerAg is affiliated with BJA Stock & Station Agents. He regularly lists and sell cattle for clients as well attending bull sales to support client purchases. Alastair provides pre-sale selections and classifications for seedstock producers in NSW, Qld, and Victoria. He can be contacted here or through his website www.raynerag.com.au