Beef Central, Genetics editor Alastair Rayner, 08/02/2022

THE record values achieved across bull sales last spring reaffirmed the commitment most commercial breeders have towards genetically improving their herds.

Looking back over a large number of sales, a closer analysis of results demonstrates stronger demand for bulls with higher EBV accuracies as well as strong competition for bulls that rank more highly in breed EBV values.

Making genetic progress is a combination of the selection intensity placed on replacement heifers, and on the accuracy of genetic information available on the bull. Higher accuracy figures are a closer estimation of a bull’s potential to improve a herd. And using bulls that are ranked among the top percentages of a breed should generally result in larger improvements in the progeny that are expected to be sired by that bull.

Among many commercial cattle producers, a key selection decision behind the purchase of a bull is to continue to lift performance in traits that are linked to overall profitability.

Looking at data presented in the Bush Agribusiness Australian Beef Report 2020 Vision, there are many areas where producers can seek to lift production.

Herd fertility is a key area, and the report suggests a 5pc increase in herd fertility can actually lift income by 7pc. Increasing the average sale weight by 5pc can increase income by up to 4pc.

In practical terms what does such a lift mean? And can this be achieved using genetic selection? In the first instance the average sale weight over a ten-year period across southern herds was published in the Australian Beef Report 2020 Vision as 431kg across all head sold.

The top 25pc of producers achieved a considerably larger 464kg across all head sold. Making up the difference of 33kg in sale weight using genetics alone is a process that will take several years to achieve.

Even a lift of 5pc on the average sale weight in southern herds requires achieving an average increase of 21.5kg.

For northern herds, the average across the same ten-year period was 408kg/head sold, and the top 25pc were achieving average sale weights of 431kg. Again, finding the lift through genetics alone is something that will take time.

So where does the new genetically superior bull fit into the target of lifting weights at sale?

As an individual bull within a breed, there are many bulls (across the breed) that have the genetic potential to increase progeny weights – perhaps not to the extent of achieving a 5pc increase on average, but certainly to see progeny weight much heavier than their siblings.

Team effort

Before this year’s calves are born and producers start anticipating the heavier weights or marked improvements they expect to see in this year’s calves, it’s important to temper expectations around a few herd practicalities.

In most cases, a new bull will not have been left to join across an entire breeding herd. In reality, for most commercial herds, a new sire, or sires join an existing bull team. Without a management system in place to identify the cows a new bull was joined with, identifying his calves will be a challenge.

A simple fact that is often overlooked is that the total number of calves born, and the kilograms of beef sold each year is a result of the efforts of the entire bull team. While a new sire may be expected to contribute significant improvements on identified traits, his overall contribution to herd productivity will be limited by the average of the bull group.

It may be that a producer will be able to identify the progeny of a new bull or bulls as a result of their management system. In this case the increased performance in traits such as growth or yield may be quite evident. When compared across the entire herd, those differences quickly become diluted and harder to identify.

Quite often producers fail to account for this averaging impact. This can lead to some disappointment if expectations are not adequately realised.

In order to temper disappointment, its worth taking the time to calculate what the average EBVs of interest will be across the entire bull team. Once this average has been determined, it’s possible to calculate what the expected progeny difference will be across the next generation of calves.

The impact of the team of sires is demonstrated across many progeny test projects. The impact can be seen from results conducted by the Australian Brahman Breeders Association and reprinted in a TBTS Technical note.

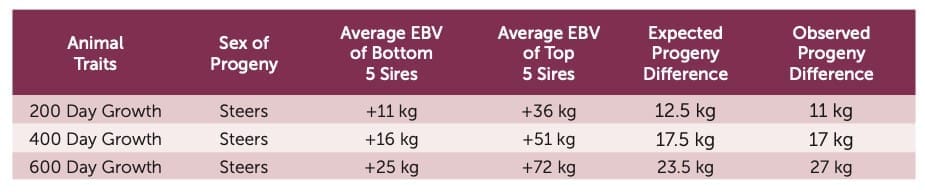

In this trial, bulls were selected as either being in the top five or bottom five sires for growth. The average across these ten sires was calculated before being divided in half (as each bull contributes half of its genetics to the calf). The expected progeny difference for 200, 400 and 600 days was determined in this table.

Source: SBTS / TBTS “Do Estimated Breeding Values (EBVs) really work?”

As demonstrated in the research, the estimations were very close to what was actually recorded in the calves.

Two messages

There are two messages to emerge from this. The first is that to make improvements it’s important to focus on improving an entire bull team and not expect a single addition to change the herd’s profile on his own.

That’s not to say replace an entire team every year. Rather, it suggests producers should have a clear objective of selecting bulls that fall within certain genetic parameters and aim to select bulls that are above average in order to ensure their bull team is constantly helping drive change in the herd.

The second is to be realistic about the nature of the change that is intended.

Increased turnoff weights across a herd are a good example. Increasing the entire herd’s turnoff weight by 5pc through genetics alone could take a number of years.

Making rapid change will require close focus on strategic management of animals, particularly in areas such as nutrition in order to fully realise the genetic value of a herd.

Achieving genetic progress requires not only a focus on the bull team. Making time to consider the selection intensity placed on replacements, and on breeders generally is also a factor.

Higher pressure helps lift herd averages which in turn complements a bull team that is, collectively genetically above average.

Alastair Rayner is the Principal of RaynerAg, an agricultural advisory service based in NSW. RaynerAg is affiliated with BJA Stock & Station Agents. He regularly lists and sell cattle for clients as well attending bull sales to support client purchases. Alastair provides pre-sale selections and classifications for seedstock producers in NSW, Qld and Victoria. He can be contacted here or through his website www.raynerag.com.au