By Alastair Rayner

I’m often asked by producers to define the traits that make cows more profitable. Its a question that many producers themselves struggle to consistently answer. Over many occasions I’ve heard replies including “fertile”, “good doers”, “have good temperament” and “reliable”. However these are generally pretty subjective descriptions that are applied to individuals and where she might place in a breeding herd.

There are of course plenty of other subjective assessments about cows. There are people who define a cows profitability often on the basis of the genetic profile of the herd. This can often be misleading as well, as genetics only plays part of the overall story of productivity in a program.

“Cows should be described objectively using measurable and manageable traits

Moving from subjective descriptions is essential in order to achieve a more productive herd. Using objective, measurable descriptions naturally leads the discussion towards managing traits. So when I try to describe a profitable cow, I look to describe a cow that has:

· The maturity pattern and breed suited to the environment and target market

· Can get into calf in the first or second cycle and carry the calf for a full term

· Calve without assistance – producing a live calf

· Wean that calf and then rejoin successfully

These are characteristics that underpin profitable breeding programs. The are also traits that producers can manage and select for in their herds. I think many breeders are challenged by using multi levels within their selection process. However it can be done very successfully and does lead to rapid improvements in a breeding herd.

At a purely practical level selection for poor performance in one of more of these areas can be straightforward. Cows that fail to go into calf or those cows that don’t wear a calf can be identified and culled. Good ID systems and a good record system are essential to help identify and remove these cows.

However this doesn’t really solve the problem of performance or improve the maternal traits across the herd. Removing one individual cow doesn’t account for the genetics that are within the herd, and that may contribute to the issue displayed by that cow. Often the decision to remove the cow is a result of the environmental effect that contributed to that result. The underlying genetic traits may still be within the parent or progeny that “got through this year”.

Individual cow selection and removal is important in any efficient herd. Non-performing cows should be removed when they are identified. However, I encourage producers to use these decisions to refine their overall breeding strategies and directions. In essence to go beyond the individual and select for traits that will contribute to a more productive cow and cow herd.

Pregnancy is a key selection tool. Ideally early detection through an accredited pregnancy tester will identify those cows that are in calf, and the ones in who have gone into calf in the early cycles. On a weight basis alone, the potential difference between calves born at the start of calving and the end of a 9-week period can be up to 56kgs. The flow on effect may mean that as a replacement heifer she will be younger and smaller than her siblings at joining, and so potentially less likely to go into calf herself.

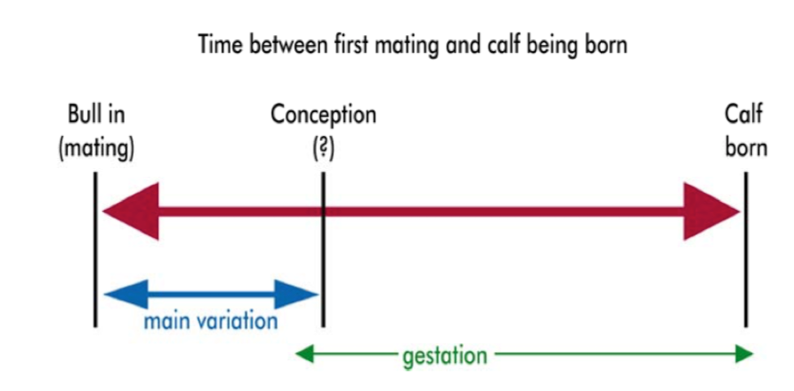

As part of a longer term strategy the genetics of a herd and its ability to go into calf early is one that producers can and should consider. Within the range of published EBVs, Days to Calving is one that can be very valuable. This EBV describes the period of time between when the bull is joined with females (the start of the joining period) until calving. It’s expressed in days.

Most variation within this trait relates to the period of time it takes for the female to become pregnant. Gestation length appears to be mush less variable. Selecting for a negative Days to Calving EBV places the emphasis on selection for animals that will conceive earlier in a joining period. Females with shorter Days to Calving EBVs also tend to be those that show early puberty as heifers.

Producers should be using their pregnancy testing results as well as calving results as an indicator of the trend that exits within their herds. If the trend is towards later, and younger calves, there is a definite opportunity to improve and make real progress towards selection for a trait that does have a practical and economic payoff.

Days to Calving is considered to be one of the more difficult traits to measure. This is frequently pointed out to me be producers! While accuracies may have been low in recent years, inclusion of genetic data through Single Step has had a dramatic impact on accuracy of this trait. Single-Step analysis includes not only pedigree and performance data, but DNA information as well. This gives a greater understanding of an animal’s potential as it now takes into account the actual relationships it shares with all other animals that have been genotyped within a breed.

In practical terms, producers looking to select for more productive cows can make immediate decisions on individuals. However the improvements in EBV accuracies for traits such as Days to Calving, mean they can also make decisions that address the underlying issues that contribute to a herds overall profitability.

By Alastair Rayner, www.raynerag.com.au

@alraynerag