Beef Central Genetics editor Alastair Rayner, 15/02/2022

AS part of my consultancy business, for the past three years I have posted a weekly feature called “Bull of the Week” on my Facebook page. The intention is to highlight the efforts of my clients who are achieving success with their breeding programs.

Often, the choice of which bull to feature comes down to a combination of the image of the bull, the background he has – including genetic information, and perhaps some comments about programs I think he would suit.

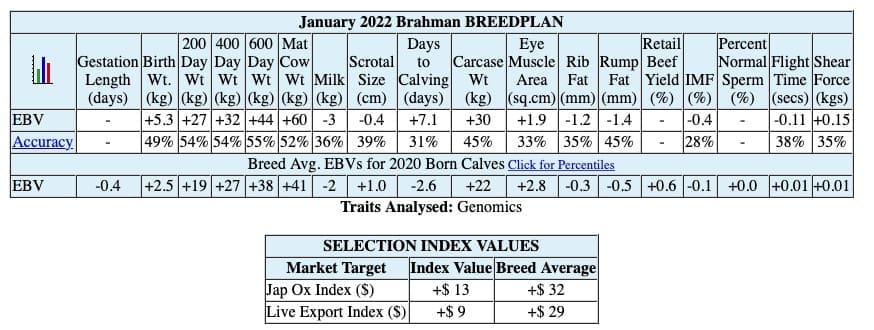

It isn’t unusual to receive some comments or questions on particular bulls featured. I recently received a message asking me to help explain why I had selected a particular Brahman bull (see Breedplan data below), as his published Estimated Breeding Values placed him in the lower percentages for many published traits and at the bottom of the breed indexes.

It was a good question, and in answering that request, it has highlighted an issue associated with how many people read the information associated with EBVs.

Importance of accuracies

When considering the information published, the table with EBVs has several key components to consider. Most people often look only at the EBVs for particular traits, and how well that compares to the breed average for the year.

However this is not the only piece of information to consider.

The second important component is to assess the accuracy of the EBVs published for the animal. Accuracies are a result of the amount of information collected for each animal, drawing on its pedigree, known performance, progeny performance and now in several breeds’ genomic testing.

Increasing data will result in greater accuracies and ultimately increase the level of confidence a producer can have that progeny performance will reflect the genetic potential of the sire.

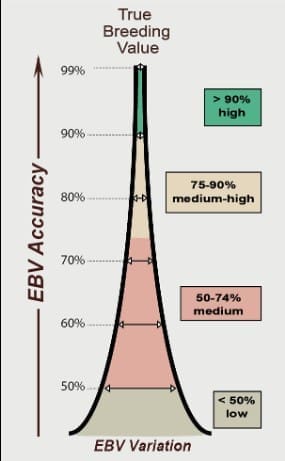

As demonstrated in this graph, as accuracy increases, the variation in EBVs reduces significantly. Breedplan describes these four accuracy percentiles as follows:

- Less than 50 percent accuracy – the EBVs are preliminary. In this accuracy range the EBVs could change substantially as more direct performance information becomes available on the animal

- 50-74pc accuracy – the EBVs are of medium accuracy. EBVs in this range will usually have been calculated based on the animal’s own performance and some pedigree information.

- 75-90pc accuracy – the EBVs are of medium-high accuracy. EBVs in this range will usually have been calculated based on the animal’s own performance coupled with the performance for a small number of the animal’s progeny

- Greater than 90pc accuracy – the EBVs are a high accuracy estimate of the animal’s true breeding value. It is unlikely that EBVs with this accuracy will change considerably with addition of more progeny data.

When considering the information published on a sire, accuracy matters. Low accuracies can and frequently do change, and this can result in unexpected progeny differences.

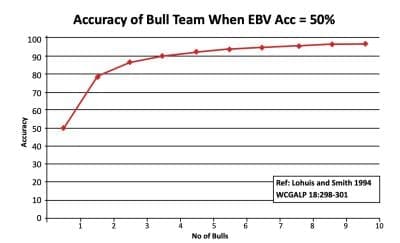

Of course, as discussed in last week’s column, using a new sire as part of a team will help address the issue of low accuracy sires. As the number of sires used within a team increases, the overall accuracy of the team is also increased.

The final piece of information to review is the traits that have been recorded. This is published below the EBV table and offers some insight into what traits may have been recorded and how they have contributed to the generation of the published EBVs.

Sample EBV Information for a young Brahman sire

Examining the information provided on the Brahman bull in the table above, it can be seen the traits analysed are the result of genomic testing only. No other traits have been recorded on the animal itself.

The value of genomic testing is in its capacity to generate EBVs on young sires. In this case, the EBVs would have been generated using any known pedigree information along with the information that the genomic test has provided. The animal in this example has yet to generate progeny and so across the board the information available for the creation of EBVs is limited compared to an older sire.

Without doubt if this sire is used in programs where information can be recorded on his progeny, as well as information from other links, the overall accuracy of each EBV as well as his index values will change.

The issue for breeders who read catalogues without considering all the information on offer is they could easily overlook a sire who may actually have the genetic potential to make some effective change in their herd.

While a bull with high accuracy figures – but low rankings for traits against the breed average is not really suited to rapid genetic progress, young sires can be a bit different.

In the instance where accuracy is low and traits recorded are limited, some discretion may be advised.

If a young sire is being used as part of a team, this can also offset to some degree the lower accuracies of the individual and potential achieve the genetic outcomes producers are seeking.

Alastair Rayner is the Principal of RaynerAg, an agricultural advisory service based in NSW. RaynerAg is affiliated with BJA Stock & Station Agents. He regularly lists and sell cattle for clients as well attending bull sales to support client purchases. Alastair provides pre-sale selections and classifications for seedstock producers in NSW, Qld and Victoria. He can be contacted here or through his website www.raynerag.com.au